How do you queer art history within the museum space? How can we make queer artists’ legacies visible without tokenizing their identities?

Can we make historical queer aesthetics and expressions relevant to a contemporary audience while admitting that giving them LGBTQ labels is anachronistic? Whose authority is it to define queer art, anyway?

Within a institution which has been complicit in queer censoring for so long, which issues will be raised around queer curating?

Made to coincide with the 50th Anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK, Queer British Art – 1861 to 1967 at Tate Britain raises more questions than answers. Both in its representation and interpretation, the exhibition curator Clare Barlow sought to make art through a queer lens accessible to a wider mainstream audience. However, the deeply personal messages behind the works and the political activism associated with the term “queer” were often lost in translation because of this, as were radical, alternative proposals around gender and sexuality.

The exhibition starts with a selection of 19th century art playing with the notion of aesthetics and implied homoeroticism. Simeon Solomon’s Sappho and Erinna (1864) expresses his own sexuality in veiled terms while Leighton’s languid male nudes reflect the ongoing ambiguity around his own preferences. In both cases, the utopia of Ancient Greece in these paintings becomes a way to reassess queer relationships in a fantasy space. In Evelyn Pickering De Morgan’s Aurora Triumphans (1877), veiled Night leaves Aurora suggestively dazed and tangled in loose bonds. She was modelled by Jane Hales, whose relationship with De Morgan despite her marriage would not neccessarily have been seen as queer at the time. The “scandal” around William Blake Richmond’s The Bowlers (1870) does not relate to semi-naked women embracing but rather their presence at a game full of nude men. The works express a queer sensitivity in themselves, regardless of sexuality: there is a sensuous, camp and almost kitsch appeal within their subject-matter and execution which encourages us to look closer, finding new details in form as well as content.

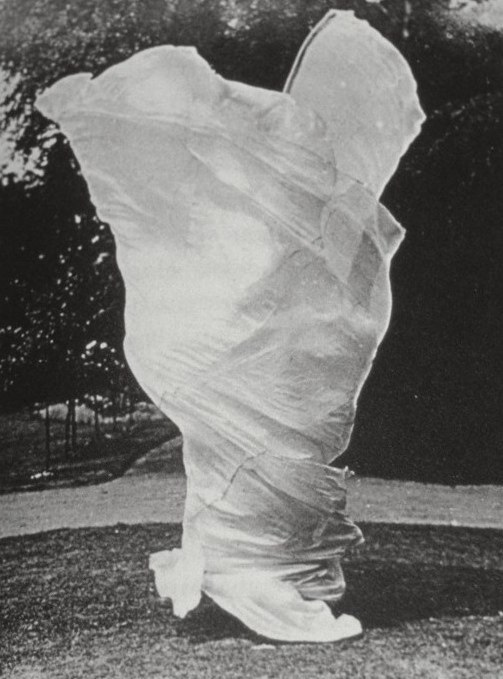

The literature and theatre displays which follow detract from the focus on queer visual art to deliver more context around queer social history. The door of Oscar Wilde’s prison cell has some historical relevance as do items exploring the relevance of performance and drag within queer culture. As interesting as these artefacts are however, they do not always link back explicitely to influence on visual art production, save for two artists in particular who crystallize the impact of the respective genres on their art as intended. The first is Aubrey Beardsley with his fantastical queer erotic drawings either illustrating or parodying literary texts. The second is Una Troubridge and her bust of Nikinsky, whose rendition of “Afternoon of a faun” created shockwaves through the ballet scene for its raw sensuality and aesthetics breaking up traditional performance conventions.

The “Bloomsbury and Beyond” room was strangely the one in which I felt least engaged by the art on display despite the presence of Duncan Grant or Dora Carrington “queering domesticity” in the exhibition’s terms. Duncan Grant’s modernist aesthetics and queerness are explored in his depictions of bathers, meant to relate to fantasies about filling ponds with men (many can relate, I’m sure). For me however, only Duncan’s Erotic Embrace really delivers what I feel the display was trying to convey: the sense of tenderness in an explicitely homoerotic scene, with an intimacy and quiet reinvention of relationships within the home and outside the norm.

Increasingly, I felt the works in the exhibition were often at risk of becoming illustrative devices for historical and biographical enquiry and assumptions around the artists’ queerness, whereas the works should act as queer works of art in themselves. For instance, Ethel Sands’ painting Tea with Sickert (1911-12) shows the scene of Sands and her artist partner Nan Hudson facing Sickert during one of their many visits but aside from the interesting facts about the couple, the painting itself feels devoid of any particularly charged queer meaning. This is very much a text-based exhibition, but while context and interpretation are key, the works should also speak for themselves. I would argue that it is reductive to assume a work is queer based on an artist’s identity or its portrayal of a queer artist. Nevertheless, there was an inventive addition to the labelling – the frequent intervention of external voices from current members of the LGBTQ communities. I would have liked to see this more – not only voices of assent but critical and contrasting views on what this particular representation meant for them.

The exhibition’s portrayal of blackness is limited to Glyn Warren Philipot’s Henry Thomas (1934-5) and Edward Wolfe’s Portrait of Patrick Nelson (1930s). The first is accompanied by the knowledge that this model is also in fact his servant, making the portrait an uncomfortable romanticization of racism and classism as well a queer document. The second is more compelling as an artist’s representation of his lover Patrick, a law student he met in London who was also involved with Duncan Grant. This feels like a moment where the “British” label should suffer transgression for the sake of nuance. The short but powerful essay in the catalogue by Kobena Mercer mentions gay black artist Richmond Barthé as one of the catalysts of the Harlem Renaissance, and furthermore draws upon Isaac Julien’s inspiration from Philipot to create the iconic Looking for Langston around queer, black modernist desire in the 20s-30s.

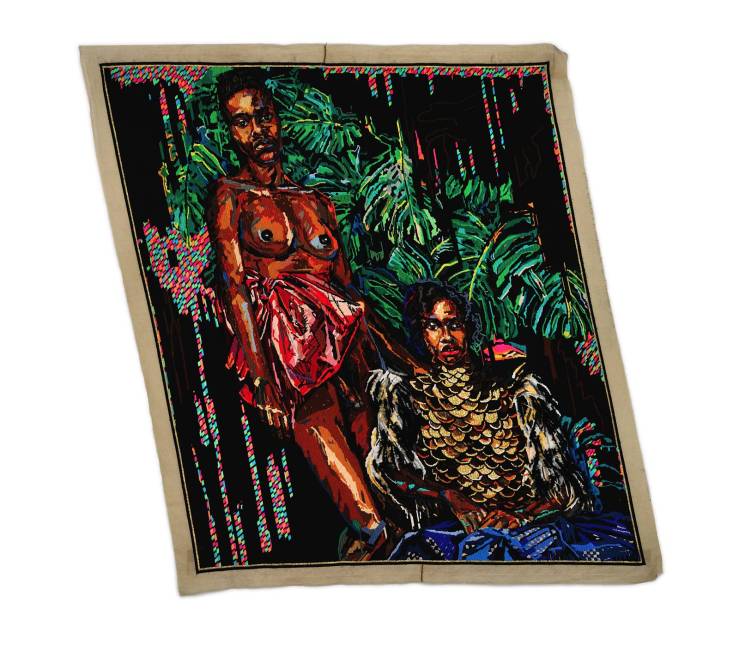

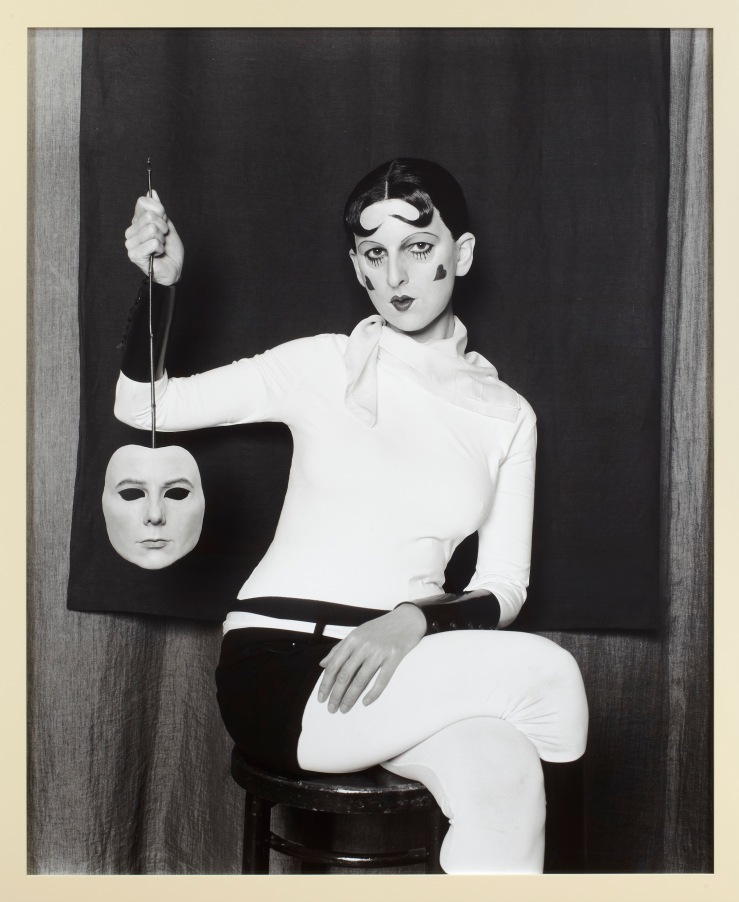

The strong lesbian representation or lack thereof is disappointing on many levels because it skims the surface of its potential and its inspection with feminist art practices at the time. Gluck’s defiant self-portrait is powerful in showing that gender non-conformity and artistic identity conflated with her queer identity, as it did for many other lesbians and bisexual women in interwar Europe. However, Gluck’s sole other contribution is a still-life of flowers dating from her relationship with a flower arranger, which feels strange considering her powerful portraiture and what it could have brought to the exhibition. The quaint gazing of women at nudes represented by Laura Knight or Dorothy Johnstone hints at something that was going to become essential in the creation of the modern, feminist artist – the possibility for new spaces for women to interact and collaborate away from men, reclaiming and repurposing the artistic gaze as female – and queering it in the process. However it feels as though the works themselves do not do this notion justice, skirting around assumption and coyness as do the labels. There was a need for queer women to reclaim their own sexuality as a revolutionary act rather than a Victorian stereotype of platonic, sexless “marriage”, but the exhibition does not give room for more explorations around this theme. Dora Carrington’s female nude is beautiful in its sensuous execution, but it feels strange to assume that any relatively sensual nude should be seen as queer just because its artist identified as bisexual (“hybrid” in her terms). It feels strange to have a label admit that we can neither confirm nor deny lesbian undertones in an anonymous nude study when there exists a loving, erotic nude portrait of her lover Henrietta Bingham as a possible alternative, Reclining Nude with Dove in a Mountainous Landscape. Overall, it is confusing that the display for queer women feels so sparse when the interwar period was a thriving moment for them both on a literary and artistic level linked to new opportunities for women artists as well as feminist activism. The inclusion of the decidedly French Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore challenges the “British-only” theme – so why not include other lesbian artists working in Europe such as Jean Mammen or Romaine Brooks, not to mention the artist couple Gerda Gottlieb and Lili Elbe?

Further on, the exploration of queerness related to urban life feels more exciting and thought-provoking. Arcadia and the Greek homoerotic ideal is revisited beautifully in Keith Vaughan’s work Kouros (1960), where the experimentation with modernist form and queer fantasy in new urban settings mingles with notions of classical aesthetics. Edward Burra’s Izzy Orts depicting US sailors in American bars encapsulates the new, giddy access of queer men to an urban nightlife to experiment sexually and trangress social public norms. The last room of David Hockney works facing Francis Bacon works had two queer visions clashing and contrasting both in terms of form and content. Portraiture pervades the exhibition, from Pennington’s iconic Oscar Wilde portrait to depictions of Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolfe and Vernon Lee. However, literally documenting these queer representations does not neccessarily give us further insight into queer art practices and senstivities. This is amended with Francis Bacon’s Seated Figure representing his former lover Peter Lacy, David Hockney’s cheeky portrayal of the drag queen Bertha alias Bernie (1961) and Angus Mc Bean’s photograph of his occasional lover Quentin Crisp. They express this variation in queer relations and attitudes, from violence and provocation through to senstivity and love. This said I would have loved to have more focus on modern queer artists I knew less about – or more room to include artists from the 70s and 80s.

This is not “part” of the exhibition per say but to cut it off in 1967, before the Stonewall Riots in the 70s and the AIDS crisis of the 80s is worth commenting upon because it feels off in a British and international context. I understand that it “fits” with the anniversary the exhibition is meant to commemorate but it undermines the struggles the British LGBTQ community nevertheless endured for decades and the critical edge the exhibition could have had is lost. Section 28 brought about under Thatcher to prohibit the “intentional promotion of homosexuality” by a local authority” was only repealed in 2000. Furthermore the 60s and 70s begin the moment where queer artists not only fight back and embrace their queerness but redefine queer art as an activist act. “Queer” as a term expresses political and counter-cultural sentiment.

I discovered and enjoyed new artworks and perspectives on queer art and artists within this exhibition. For all its power and strong intentions in terms of LGBTQ visibility, “Queer British Art” still has issues in its content, artwork selection and execution and left me feeling that it could have been far more daring in its aims and message. If this exhibition was so effective in causing some outrage despite its polite tone, why not go all the way and really kick up a storm? The disruptive power of queerness is meant to subvert and challenge our traditional way of experiencing and looking at sexuality and gender. More often than not, however, it felt as though the artists were trapped by the exhibition’s themes of coding and dissimulation. Tom Powell’s interview of Richard Dodwell reacting to the exhibition captures this perfectly – a feeling that gender identity and sexuality were treated with a tongue-in-cheek playfulness rather than a matter of life or death. This is why post-1967 art and contemporary interventions would have been so much more effective in creating a conversation around visibility, censorship and queer self-expression.

The entire experience felt like a collection display with interventions disrupting and revealing queer narratives within a wider museum context rather than an exhibition with a certain chronology, conversation and narrative taking place. This is mainly because it feels as though there is a disconnect between the works themselves, whose juxtaposition is not explained or justified as much as the individual biographical contextualisation for each artist. The selection strives to highlight a queer presence which is already a part of major British collections. The Victoria & Albert Museum, the National Portrait Gallery and of course, Tate itself are there, as well as The Fitzwilliam Museum, the National Archives and a number of private collectors, libraries and archives. This raises the question: how will these works be displayed upon their return to their respective collections? Is queerness a temporary phenomenon within the museum or is it here to form long-term, lasting relationships with visitors? Will this exhibition lead to change or another form of well-meaning tokenisation? Another important point is that public programming around the exhibition was strong, at Tate Britain as well as Tate Modern, involving artists such as Travis Alabanza and Dean Atta to engage with queerness on an intersectional level including an exploration of the queer black experience and post-colonialism. However, we need to wonder why these artists and many others are good enough for one night or workshop but not enough for long-term collection and curation.

This exhibition was long overdue and an important moment in acknowledging queer culture in a mainstream museum context. This only makes its criticism all the more important in order to facilitate more curating and visibility around queer art and its infinite potential for representation and discussion. Its legacy will hopefully be seen as the first in a long line of endeavours to give queer art the representation it needs and the curation it deserves.

Queer British Art 1861-1967 at Tate Britain, until 1 October 2017.