“Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces.”

Claude Cahun

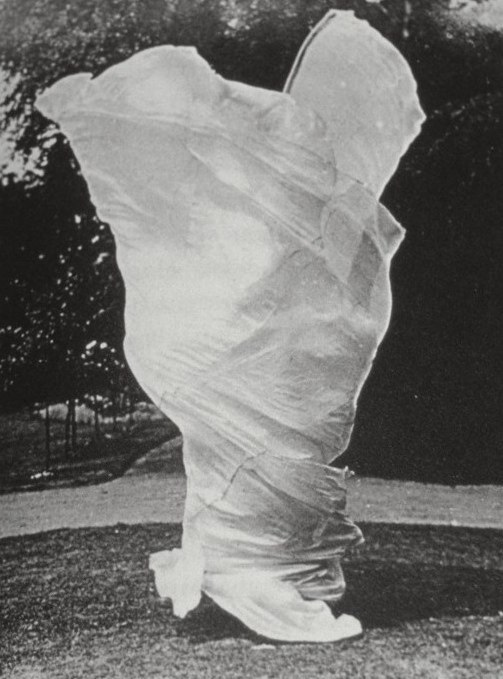

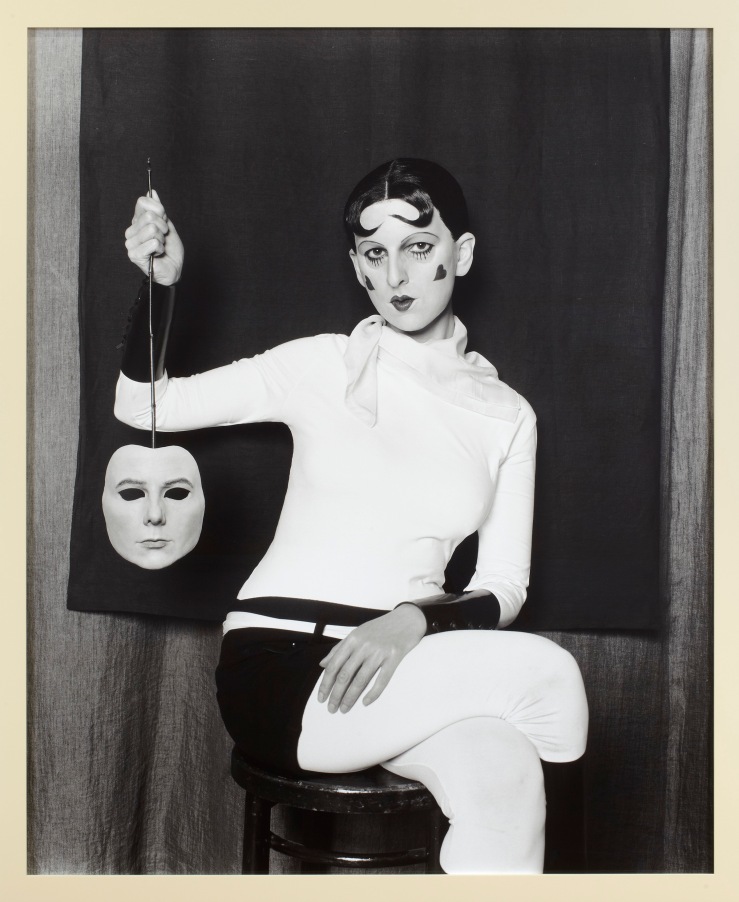

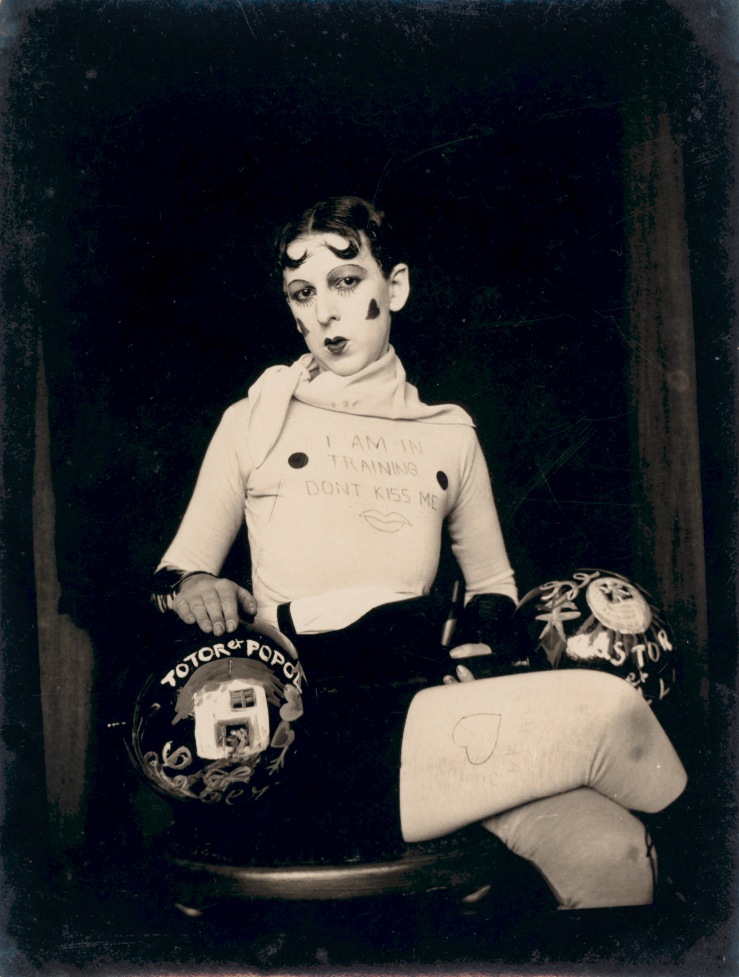

Gillian Wearing confronts us at the exhibition entrance, wearing Cahun’s face but holding her own. Opposite, Cahun gazes back in the original photograph Don’t kiss me, I am in training, circa 1927. A strong man with a vulnerable, feminine twist or a feminine figure seeking and embodying stereotypical masculine values? The artwork’s provocative power by one of the first queer photographers we know of has a subversive power and energy which has not aged in a society in which we are only just starting to talk seriously about gender fluidity and queerness in mainstream media. Wearing’s work aptly reflects Cahun’s desire to blur and disrupt portraiture and appearance by making it staged, constructed and altogether unrealiable in getting the full picture.

This exhibition had the rare appeal of being as much an intimate conversation between two artists rather than a simple tribute of a living artist to an older body of work. Death and seven decades separate 20th century photographer Claude Cahun from contemporary artist Gillian Wearing, but it feels as though their ideas have interconnected and bounced off each other with sharp clarity and insight across their respective contexts. When Wearing discovered Cahun’s work, it has already seeped into discussions around identity, feminism and gender…and Wearing had already set a course for her practice around her own image, or rather its erasure. The notion of the mask is central to her work – a disturbing and engrossing performance for the camera in which Wearing creates hyperrealistic masks of her family, friends and artistic inspirations and poses in their guise. Her eyes alone betray the identity behind the mask…but is there yet another mask to remove? And yet another?

“Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

Claude Cahun, Disavowals

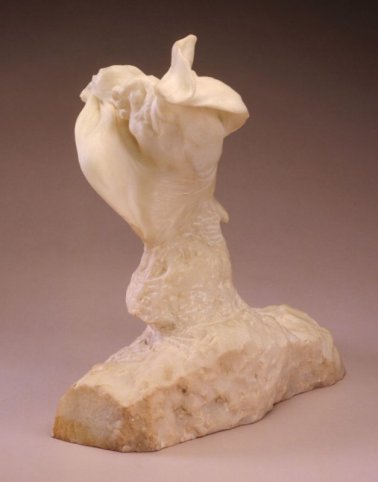

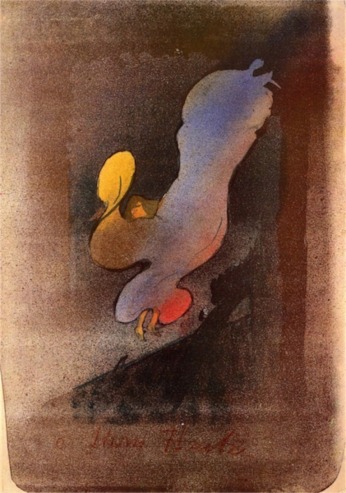

Claude Cahun was jointly a writer and a visual artist; in fact, her most important work, Disavowals, is an intimate collage of journal entries and face plates, whose visual and literary associations and poetics. Created in collaboration with her partner Marcel Moore, also an artist, photographer and writer, the book refuses to be intellectual or rational, revelling instead in dreamlike and surreal interconnections. Interestingly Cahun did not identify with the Surrealist label, even though her work is now mostly classified as such through its strange absurdist metamorphosis and collage. In the same way, there has been much debate about Claude Cahun’s “true” identity and how it may be “labelled”…in a contemporary LGBTQ+ spectrum. Is Claude Cahun a butch lesbian, trans, non-binary, genderqueer? In many ways, she is all of those things: she was in a lesbian relationship with Marcel Moore till her death and definitely identified with the butch and androgynous identity constructed by lesbian artists at the time. However, this does not mean she cannot also be seen through a nonbinary and genderqueer lens. This is the point in which it becomes complex to curate a queer and gender non-conforming artist with contemporary labels, while being well aware that the artist themself perhaps would neither have enjoyed nor identified with them. Where do we draw the line between erasure and recognition of a particular time and context? We will never know if Cahun would identify as nonbinary prefer “they” pronouns, or alternate between “she” or “he”.. Claude Cahun’s (dis)avowal as a queer artists reflects a fluid relation to gender, but this does not neccessarily disavow her ties to lesbianism in any way. Labels are meant to be scratched over, boxes upturned. Perhaps that which makes Claude Cahun the first true queer artist is the way in which she still manages to subvert and escape our expectations and assumptions…even those of LGBTQ gatekeepers. Whichever pronouns she would have chosen to use now, it is fair to say she maybe would have identified beyond the lesbian signifier available at the time and which encapsulated a wide range of butch, gender non-conforming and trans sensitivities. This is why we need to embrace all aspects of her legacy, rather than in-fight or straight-up exclude trans or nonbinary readings of her work and life. She is not herstory’s to keep jealously out of any other queer discourse or influence. Yes, it is complex. But so is identity. We need to embrace this complexity and ambiguity in full – which is why I am glad this quote was displayed within the exhibition, but somewhat frustrated it was not unpacked more in written interpretation.

“I am in her, she is in me; and I will follow her always, never losing sight of her.”

Claude Cahun, L’idée-maîtresse, 1927

There are further problems with the way in which this queerness is negociated within the exhibition, however, the first being that Cahun’s partner, Marcel Moore, deserved an equal seat at the table. Discourse around Cahun and Moore’s work together, including an excellent chapter on the duo in Tirza True Latimer’s Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris, shows their photographic and litrerary productions as a creative duo. While the exhibition curators are fine with the display of this gender non-conforming statement, there is a strange lack of mention of the context of the book itself, or of the fact it was, as much as the visual production on display, largely a collaborative work over forty years with Moore. She is mentioned in the role of the lover and partner, but sparingly. In fact, they could both be considered as both life and artistic partners, engaging in a queer and activist practice which was fighting against the largely straight-men dominated art world. The political and radical act of adopting butch/masculine-of-centre appearances and androgynous names was a bite back against not only society at large, but the artworld’s sexist and homophobic bias at the time, in which women were relegated to muses or written out as artists altogether. This also fed hand in hand with antisemitic bias and aggression in artistic circles: as a Jewish queer woman, Cahun escaped erasure and embraced resistance. With the arrival of Nazism on the Isle of Jersey on which they had escaped from Parisian centres of influence, this political resistance became even stronger – as the couple fearlessly slipped propaganda works to soldiers. Even though they were posing under their original “feminine” names and as sisters, their activities were discovered in 1944, leading to imprisonment and a death sentence stopped by their liberation in 1945. Although Moore is mentioned through this record, she is still somewhat sidelined. The problem is that erasing fully or partially Cahun’s queerness and her collaborations with Moore does not make her works less powerful in their visual quality but their intimate meaning and context are devalued and decontextualised. No, you do not neccessarily need to know an artist’s sexuality or gender to appreciate their work – which has been many people’s somewhat exhausted argument every time an institution attempts to curate a body of work which isn’t by straight white men. However in Cahun and Moore’s case this collaborative, gender-fluid work is intentionally queer and feminist in its nature, in its context and in its means of production.

“We never get to know ourselves. We are forever changing and contradicting ourselves. We’re always evolving.”

Gillian Wearing

The opposing argument would be that this is framed as a Cahun and Wearing exhibition, not a Cahun and Moore monographic exhibition. That there would a weird imbalance between one gaze and another if there was a second, more covert one to be mentioned alongside Cahun. However, I’d argue that highlighting the queerness inherent to Cahun and Moore’s work would not subsume or sideline Wearing’s work in the slightest – on the contrary, it would amplify its impact and our ability to her her transformations through a different lens, without erasing her original intentions. Her powerful imagery holds its own in vast, momentous photographic portraits which contrast beautifully with the small black and white photographs of Cahun and Moore.

The way in which Cahun and Moore’s work and life intertwine over four decades are immensely relevant to the way in which queerness in the early 20th century becomes not tied to what you do in your relationships and behaviour but to who you are and how you perform this existence. Their work was intimate and autobiographical, a record of imagined personas which both placed another mask upon her and revealed only a facet of who Cahun was in these phorographs.

In contrast, Gillian Wearing focuses on “real” people which are deconstructed and made to feel “unreal” in the way in which Wearing meticulously wears their faces and adopts their postures. Wearing’s portrait as her brother is particularly arresting, as her body is transformed through cosmetics, prosthetics and posture. Similarly, her portrait as her father operates a metamorphosis in imagining a time before her own existence, through old photographs. It would be strange to call these “cross-dressing” in any way. While Cahun tries on different identities without ever revealing the face behind the mask, and confronts the heteronormative gaze with butch and andronynous power, Wearing allows herself to become absorbed by them. Somehow even more disturbing are the explorations of images of her younger self, the illusion disrupted by the gaze of the older self within the face of a child. The sight is strange and unsettling. While Cahun reveals fragments of identity through her performance, Wearing does everything she can to remain hide herself, by solely constructing her identity through the visual presence of those which “made” her who she is. Her fight to reach perfection in recreating a portrait perfectly regardless of gender, age or identity is mesmerizing. It both reveals the efforts we take in creating gendered and “solid” representations, and their flimsiness. I loved Wearing’s sincerity and commitment to her practice, her playfulness and strength, her paradoxical vulnerability in laying herself bare while hiding her face. This vulnerability reaches full circle in the last room. The exhibition led towards Wearing sponatenously revisiting what linked her to Cahun. Here, the face is hidden. There is no representation, no appearance, and in doing so Cahun and Wearing are one and the same.

Despite its shortcomings on some of the context of Cahun and Moore’s work, this exhibition acheives the rare feat of allowing the conversation to work both ways, confronting and subverting our ideas of appearance, gender and identity. In many ways, I think that it could have amped up the volume. Cahun and Moore’s work has inspired an entire generation of artist photographers and artists, particularly women, is a staple of queer and feminist art history and discourse and has done so on feminist and confrontational grounds unseparable from their defiant queerness. Her work needs to be shown outside of the “Surrealist” context into one resonating with contemporary concerns. To acknowledge so does not exclude the presence of other artists outside of the LGBTQ+ spectrum. However, it will introduce a structure which operates around subversion and reframing, provoking and challenging to its very core. Cahun and Moore were well ahead of their time, and fearlessly so. Let’s celebrate this defiance by giving them even more engaging and fascinating contemporary artists such as Wearing to talk with around issues of activism, gender, queerness and feminism.

Further reading:

Tirza True Latimer, Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris

Tirza True Latimer, Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions, Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010